Unique challenges of universal mandated reporting of rural child abuse

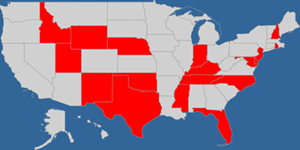

Universal mandated reporting (UMR) in these states extends beyond the requirements of medical professionals, teachers, and social workers to include every adult citizen of the state. Such mandated reporter laws pose a unique challenge for rural child welfare professionals, particularly in rural states such as Idaho, Mississippi, Wyoming, and Oklahoma, where the geographic area dwarfs the population concentration.

Universal mandated reporting (UMR) in these states extends beyond the requirements of medical professionals, teachers, and social workers to include every adult citizen of the state. Such mandated reporter laws pose a unique challenge for rural child welfare professionals, particularly in rural states such as Idaho, Mississippi, Wyoming, and Oklahoma, where the geographic area dwarfs the population concentration. Contemporary social work curriculum has been criticized for focusing primarily on urban and suburban policies and procedures, while rural standards pose different challenges for professional social workers. One emerging pedagogy is a focus on specific competencies for rural social work, including respecting the culture and intersectional identities of citizens in rural areas. Beyond the challenges of resources, relationships, and remoteness, rural social workers must recognize and understand sociocultural mores in order to effectively provide services for local families. This is further complicated by the difficulties in recruiting and maintaining child welfare workers in rural areas, where the jurisdiction may include both a wide geographic area and also an array of sociocultural norms.

Providing anonymity for the report and reporter also proves problematic for rural child welfare investigators. While most states have laws that protect reporters’ identities, rural communities pose obvious logistical problems for enforcing such statutes. Not only do residents of rural areas often know each other but they also recognize a professional social worker as an outside authority figure. This leads to further safety concerns for rural social workers who are investigating suspected child abuse and neglect. However, the argument against anonymous reporting is that rural community members often know local families intimately and are therefore able to provide identifying details of abuse and neglect. This increases the likelihood of the report’s veracity.

Putting a deadline on UMR and investigating further complicates the issues faced by rural child welfare workers. While most states require immediate reporting, each allegation must be investigated by a social worker within 24 hours. For the rural social worker whose practice covers a vast geographic area, this standard can prove unreasonable, contributing to the burnout and high turnover rate among rural child welfare workers.

Despite these considerations, UMR sounds like a useful policy at face value, one in which more eyes on children results in greater protection from childhood abuse and neglect. But the question remains: Does a system in which more reports are taken result in finding more cases of child abuse or neglect based on state law? States with UMR do not necessarily receive more per capita reports than states without it, and UMR can actually lead to a decrease in reports by professionals, who assume others will report suspected child abuse and neglect. In fact, there is no significant difference in substantiated reports of child abuse and neglect in states with UMR versus states that do not have UMR.

Furthermore, some researchers have criticized UMR laws for creating undue overreporting of suspected incidents in rural areas, all of which must be investigated. The language of the law also has a direct effect on the report itself. For example, Oklahoma’s statute reads that failing to provide “adequate” housing, food, and emotional support is cause for a report. This is open for interpretation among investigators and their superiors, who are the most significant factor in a child welfare worker’s decision to substantiate a report. Faced with a territory that covers both urban and rural areas, child welfare supervisors may not recognize rural sociocultural parenting norms. Additionally, surveillance bias, in which a child welfare worker is more likely to substantiate a report simply because the report is made, is difficult to overcome, even for professionals.

While false reporting can be prosecuted as a crime, failure to report suspected child abuse and neglect is more often addressed by law enforcement and child welfare workers. Failure to report suspected child abuse or neglect is typically a misdemeanor. Meanwhile, false reporting is subject to investigation by child welfare workers, placing yet another burden on these professionals, who then turn over their results to local law enforcement. With child welfare workers prioritizing investigations of suspected abuse and neglect and agencies like DHS already understaffed across vast rural areas, determining false reports is a low priority that often goes unaddressed.

“Rural areas have many resources for child welfare,” says Johnisha Mpadi, a child welfare worker in Oklahoma. “DHS has partnerships with local agencies in rural counties to provide great support for families. However, when it came to investigating reports of abuse and neglect, we were all stretched thin, including rural law enforcement. Often I would get a late afternoon call to investigate an incident two hours away. In rural areas, there are always more families in need than available support, and it leads to high burnout and turnover for child welfare workers and those who provide support to rural families.”

UMR is a complicated policy to enact and enforce, particularly in rural states. Rather than spreading responsibility among all citizens, as UMR statutes are written, the burden still falls heavily on rural child welfare workers. In rural areas, UMR policies may inadvertently create bureaucracy in child welfare agencies and unwittingly direct resources away from families in need. Already understaffed, child welfare workers in rural areas experience burnout and high turnover rates. Rural states with UMR laws require an approach that addresses the unique challenges of rural families and child welfare workers so vulnerable children do not get lost in the shuffle.

Erika Stone-Burnett is a University of Oklahoma Foundation Scholar and freelance writer. She studies organizational culture at the Hope Research Center.

Daniel Pollack is an attorney and professor at Yeshiva University's School of Social Work in New York.